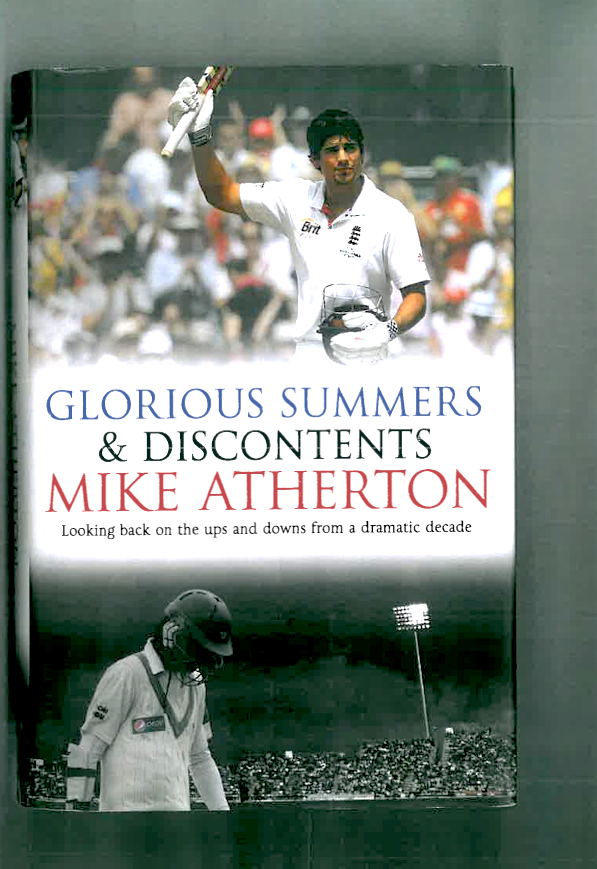

Glorious Summers & Discontents, Mike Atherton

And so it has come to this. A farce whose origins sprang, as Malcolm Speed, the chief executive of the International Cricket Council (ICC), said at the time, from a series of entirely avoidable overreactions”, has finally reached its conclusion just over a year later at the Central London Employment Tribunal. And if the ICC have many more disastrous days, such as they endured on Friday – the start of, in David Cameron-speak, “The Great Darell Hair Fight-Back” – it might be a seminal moment for the future of the administration of the game.

And so it has come to this. A farce whose origins sprang, as Malcolm Speed, the chief executive of the International Cricket Council (ICC), said at the time, from a series of entirely avoidable overreactions”, has finally reached its conclusion just over a year later at the Central London Employment Tribunal. And if the ICC have many more disastrous days, such as they endured on Friday – the start of, in David Cameron-speak, “The Great Darell Hair Fight-Back” – it might be a seminal moment for the future of the administration of the game.

Earlier in the week, Hair had not had a particularly good time of it in his attempt to sue the ICC for racial discrimination. He was cross-examined brutally by Michael Beloff QC and suffered a blow on Thursday when his chief witness, Billy Doctrove, cited “personal reasons” rather than front up, as he has promised to do.

But on Friday it was the turn of three of the ICC directors – Sir John Anderson (New Zealand), Inderjit Singh Bindra (India) and Ray Mali (then the South African director, now the president) – to face cross examination by Hair’s lawyer, Robert Griffiths QC. What a time of it Griffiths had! Turning to the gallery with a malevolent grin every time a point was scored, he revealed completely the vacuum of leadership at the heart of the organisation that purports to run the game.

One by one these well-meaning, certainly not racist but undoubtedly bumbling and, on tis evidence, incompetent administrators shuffled to the front of the room, raised their right hands and promised to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth. One by one they were sent packing, lacerated from head to foot by Griffith’s ordered mind and razor tongue. Only Bindra retained any sense of clarity of thought, sticking resolutely to his line that “the game had to go on!” and “no man is bigger than the game!” By then it was too late; the damage had been done.

Things began badly. The stenographer failed to turn up and the parties retreated until she did – all except Anderson who, perhaps unaware of the fires of hell he was about to descend into, chose to pass his time playing Sudoku. If it was a ploy to ease his nerves or order his thoughts, it failed miserably. The day before, Anderson had given evidence and, according to one who was there, he didn’t wear his pomposity lightly. How he visibly shrivelled before Griffiths, refused to look him in the eye, and developed a frog in his throat the size of which Iain Duncan Smith would have been proud of.

Anderson’s was the key evidence of the day, because it was his three-man sub-committee who chose to ignore the recommendations of the paid executives, Speed and David Richardson, and decided to remove Hair from the elite panel, made up of the representative from Pakistan (who, it might be said, was a little compromised), the representative from Zimbabwe (who had publicly supported Pakistan’s stance and who represents one of the most flawed sporting bodies in world sport) and Anderson himself, who had described Hair;s action at The Oval a year ago, as one of the most “appalling” he had witnessed. “Mr Hair didn’t stand much of a chance, did he?” said Griffiths.

Nor did Anderson. How Griffiths wanted to know how his three-man committee had come to their conclusions. It appears they did so over a jolly lunch. And then, Griffiths wanted to know, how did they persuade the board of directors to accept their recommendations? They did so in discussions that lasted less than 5 minutes. Griffiths was incredulous. “Five minutes!” he thundered, leering at the gallery. “Five minutes! And on that basis Mr Hair lost his status as a Test match umpire!”

Now Griffiths performed the impossible. I had wondered whether Speed might be a villain of this piece, given his undoubtedly shabby treatment of Hair in the aftermath of The Oval fiasco (you will recall how speed revealed Hair’s private emails). “How much weight”, Griffiths wanted to know of Anderson, “did you give to Speed’s recommendation [not to take further action against Hair] given his immense experience in cricket, and,”Griffiths added in a kind of conspiratorial, masonic way, “given his experience in the law?”

“I disagreed with him,” said Anderson.

“You gave his recommendation no weight, then?”

“I disagreed with him.”

It was suddenly apparent that had Speed been making the decisions this whole sorry mess would have been avoided. At a stroke, Griffiths has transformed Speed into an administrative god.

Anderson admitted that Hair was an excellent umpire; that he had not been given due process over his individual rights, and that the code of conduct and the principle of natural justice had been ignored, and that the reputation of the ICC and the game was paramount. Then came the coup de grace.

“Did you attend the final of the World Cup, Sir John?”

“I did not.”

“Is it important that an umpire knows the laws of the game?”

“It is.”

“You are aware, of course, that the umpires who officiated in the final made a complete bodge of it?” (Griffiths spat out the word “bodge” with great emphasis to the amusement of the gallery.) “Did they bring embarrassment beyond belief to the ICC?”

“They did.”

“And are they still umpiring?” Anderson mumbled something inaudible in reply after which Griffiths extended his mercy. Anderson went back to Sudoku, a far less taxing undertaking.

I had little sympathy for Hair during the events at the Oval, but I rather hoped the tribunal chairman (this whole process has as Orwellian ring to it) finds a way of recognising that Hair has been treated appallingly since then, while throwing out the racism claims. By bringing a claim based on racism rather than constructive dismissal his compensation, if he wins, will be much higher than if he simply sued for constructive dismissal – a weakness that has undermined his stance throughout. But instinctively I find myself sympathising with the individual and the powerless over the corporate and the powerful. This is not about what happened at The Oval, but what had happened since. There is no doubt that Hair has been treated poorly.

Beyond these narrow confines, perhaps the lasting effects of this case will be the governance of the ICC. It was clear on Friday that decision-making should be left to the professionals, to the paid executives, rather than to the well-meaning amateurs.

Nothing summed this up more than the cross-examination of Mali. He was asked what the primary role of an umpire was, to which he replied that an umpire has certain responsibilities inside the boundary rope and certain responsibilities outside it. Would he like to elaborate? For an instant, Mali looked like he had been asked to describe the internal workings of his wristwatch. Then he declined to say anything further, except that he felt Hair could resume his responsibilities as an elite umpire in the future. At that point every man jack in the room, possibly even Robert Griffiths QC, wondered what the hell they were doing there.